A Picture is Worth A Thousand Words

Consider the idiom “A picture is worth a thousand words.” This is an idea one can find singular instances of in the far past, but its readymade stature was not achieved until the first decades of the twentieth century in multiple advertising venues in the United States. We all know what this idiom is asserting: that information contained in a single image taken in at a glance is more effective than a thousand words conveying the same idea. We can get at the “unintended” idea quickly by focusing on the word “worth.” To wit: what is the worth in words of an image?

This reversal was key to Roland Barthes’ exploration of photography in his book, Camera Lucida. He did not try to find an image that would economically express his words, but he used his words to bring out something crucial about the nature of photographs (and, by implication, the nature of all images as well as dreams). He distinguished between the “studium” and the “punctum” of a photograph. The studium is what the photographer intended and typically is what we “see.” We get it, in an instant. But Barthes says it is the punctum that makes the photograph “exist” for him. This exists is then Barthes’ inner, subjective (psychic) experience. Elucidating this phenomenon requires Barthes to use words, lots of words, which an “image” cannot do.

I once wrote that “images are stories stopped in time.” To continue the story, will require either more images or words to tell the stories. Notice the plural here. While the image itself is singular, the potential stories are many and varied. The same is true of dreams. The dream is singular, but the potential stories are innumerable.

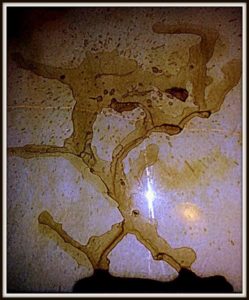

To illustrate.

Consider the following image.

One form of response is “criticism,” that is, an attempt to explain, interpret, and understand the image and to articulate its value and meaning or lack thereof. But as Baudelaire insisted, the only proper “criticism” of a work of art is another work of art. And the origin of this future work of art lies in the psyche of the viewer. Note I do not limit this to the conscious experience of the viewer. The unconscious will be viewer too!

So, then, as you look at this image, what begins to move in you in the form of “story” or “poem” or “drawing” or any other form of expression? Will it be taken up in your dreams?