Dreamsmithing

Smithing, in its most limited sense, is the art of working metals into useful objects or forms with aesthetic value. This sense of the artful use of something takes the word beyond the province of metal work and into forms such as “wordsmithing” and “songsmithing.” In this post I want to focus on the idea of “dreamsmithing.”

In metal smithing, the “work” consists of various activities such as forging, smelting, refining, hammering, filing, in addition to more specialized processes (e.g. robotic machine tooling). Hard work, and what is “worked” is always the metal, or stone, or whatever material the artist—the smith—happens to be working on.

In metal smithing, the “work” consists of various activities such as forging, smelting, refining, hammering, filing, in addition to more specialized processes (e.g. robotic machine tooling). Hard work, and what is “worked” is always the metal, or stone, or whatever material the artist—the smith—happens to be working on.

The first thing to consider about dreamsmithing, as I want to use this term, is that it is an art. It is an art that works with what a dream presents. Dream as metal, dream as materia.[1] Most people who pay any attention at all to their dreams, generally focus on trying to discern the meaning of a dream. Often this search for meaning takes the form of seeking the help of a professional dream worker whose work comes in the form of interpreting the dream to achieve the sought-after meaning. Hard work of a different kind.

Interpretation and meaning are like the utility function of metal working: the making of useful things like knives, swords, plates and cups. It is useful to get the message of the dream in the form of meaning. This utility serves the ego in various ways: bringing insight, motivation for change, a sense of personal growth, relief from suffering, a sense of purpose. Most people who relate to dreams at all use dreams in relation to these conscious intentions. This is natural and cannot be gainsaid.

What then of the aesthetic aspect of dreamsmithing?

Some years ago, while in Florence, I visited the Galleria dell’Accademia, intent on seeing Michelangelo’s David. As one enters the main hallway, one sees David standing resplendent in the yellow light of the rotunda. The statue was a magnet drawing me to it. Like others, I took pictures of David from all angles, all the while feeling that my obsessive gestures were covering over a deepening anxiety over something not done. Michelangelo had brought this magnificent figure into the world out of stone. I was reduced to taking its picture, an uneasy dependency on his creation. The more I clicked, the more I appropriated his creation, the more I felt I was doing something inappropriate.

Some years ago, while in Florence, I visited the Galleria dell’Accademia, intent on seeing Michelangelo’s David. As one enters the main hallway, one sees David standing resplendent in the yellow light of the rotunda. The statue was a magnet drawing me to it. Like others, I took pictures of David from all angles, all the while feeling that my obsessive gestures were covering over a deepening anxiety over something not done. Michelangelo had brought this magnificent figure into the world out of stone. I was reduced to taking its picture, an uneasy dependency on his creation. The more I clicked, the more I appropriated his creation, the more I felt I was doing something inappropriate.

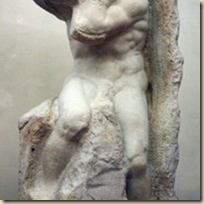

As I was leaving the Galleria, feeling more despondent than elated, I finally saw what I had neglected to see upon entering. Lining the entrance hall were a number of Michelangelo’s unfinished statues. I was transfixed to the point of forgetting, forgetting to capture them with my camera. They were rough figures, struggling for existence, as if trying to escape their stone prison. I sat down next to one of these figures and touched it, touched what Michelangelo had touched and chiseled. I felt an overwhelming urge to kiss the stone! I was feeling love.

As I was leaving the Galleria, feeling more despondent than elated, I finally saw what I had neglected to see upon entering. Lining the entrance hall were a number of Michelangelo’s unfinished statues. I was transfixed to the point of forgetting, forgetting to capture them with my camera. They were rough figures, struggling for existence, as if trying to escape their stone prison. I sat down next to one of these figures and touched it, touched what Michelangelo had touched and chiseled. I felt an overwhelming urge to kiss the stone! I was feeling love.

If we take seriously what Michelangelo said of his sculptures, then we must conclude that a piece of stone carries within it an image which is revealed through the artist’s imagination and then “freed’ into existence by the sculptor’s chipping away the stone prison. It is as if the image in the stone calls to the artist through the imagination and sets the artist on a quest to bring the image into existence.

Are these elements of Michelangelo’s “stonesmithing” applicable to the aesthetic aspect of dreamsmithing?

I believe so. In many ways, the dream as such is like Michelangelo’s raw stone. We are not satisfied with the dream itself either from the perspective of utility or of art. This dissatisfaction is what motivates the search for meaning, the seeking of interpretation, as well as “something else.”

For Michelangelo, there is something within the stone. Likewise, there is something within the dream. This something, whether in stone or in dream, is revealed through the imagination. This is what led Jung to discover what he came to call “active imagination.”[2] When imagination leads the way (in contrast to conscious intention), something is revealed that could not have been anticipated by conscious expectation. Then, “working” with these revelations, like Michelangelo’s chipping away stone, becomes the task of the dreamsmith. The hidden something within a dream can be missed. It is often little more than an inchoate “call,” and is often lost altogether as one pursues meaning.[3] It is only through imagination that this call can be “magnified” to form the substance of a “quest.”[4] The quest, inherent in the dream, cannot be arrived at from the more utilitarian aspects of dreamsmithing. It can only be revealed through the process of imagination, brought to bear on the dream.

Another difference between the utility and aesthetic aspect of dreamsmithing is that utility tends to keep one rooted to what is already known, while the aesthetic aspect always brings something that orients to the future. Jung’s collected works and seminars, are good examples of the utility aspect of dreamsmithing. His Redbook is an extraordinary example of the aesthetic aspect of dreamsmithing. As Jung noted, his prolific public work had its roots in the imaginal experiences of his aesthetic dreamsmithing. This is a good example of how the future is born from the imagination.

[1] One might argue that the dream is already “crafted” in its presented form, that we are already seeing the results of artisanal forces at work in the making of the dream, already worked, smithed into the forms we see by an unknown dreamsmith. This aspect of dreamsmithing will be the subject of a future post.

[2] In principle, the use of imagination as a way of discernment of the hidden, has a long history in many traditions and can be found at work in all areas of human endeavor, albeit at the fringes rather than at the center where the application of rational modalities and conscious intentionality is privileged.

[3] A good example of the “call” of a dream can be found in my essay, “Words as Eggs.” In Words as Eggs. Everett: The Lockhart Press, 2012. See the way I approach the utility aspect of dreamsmithing (p. 92-94) followed by the results of more imaginal dreamsmithing.

[4] As an example of a quest induced by a dream, see “I am your grandfather…”: Dreams, Synchronicity and the Future. http://www.ralockhart.com/Morpheus/I%20am%20your%20Gradnfather.htm